Translating Facebook content from Mandarin to English using automated tools resulted in significant discrepancies in users’ perception of the content’s harmfulness. In a survey, subjects were presented objectionable (green) and neutral (blue) content in English translation and the original Mandarin and asked whether the content violated Facebook’s community guidelines.

- Automated Translation and Content Moderation: Facebook's reliance on automated translation tools for moderation of non-English content can lead to significant inaccuracies. This impacts the platform's ability to accurately judge the harmfulness of non-English content, often resulting in wrongful removal or improper oversight of problematic content.

- Disparities in Perception: The study found that English-speaking reviewers perceived the harmfulness of translated non-English content differently than native language speakers. This may create a linguistic inequity where non-Western users are disproportionately affected by Facebook's moderation practices.

- Participatory Approach Recommendation: The research suggests that Facebook incorporates a participatory content moderation approach, where local language users can contribute to moderation decisions via surveys. This aims to mitigate the inaccuracies caused by automated translations.

- Global Challenges in Content Moderation: Facebook faces challenges in moderating content in multiple languages, especially in regions like India and the Mandarin-speaking world. Automated tools and outsourced moderation practices often fail to capture local nuances, leading to further inequity.

- Survey Results: In the survey, we compared English speakers’ perceptions of translated content with Mandarin speakers' perceptions of the same content in Mandarin. There was a statistically significant difference in how the two groups viewed the permissibility of the content, highlighting the risks of relying on automated translation tools.

Abstract

Facebook has long faced criticism for seemingly arbitrary content moderation decisions [1]. A leaked document in the FBarchive database revealed that Facebook employs automated translation tools to translate non-English content into English in order to enable English-speaking reviewers to make content decisions. The use of automated translation tools can yield inaccurate translations, increasing the chances that non-English content will be wrongfully taken down and that problematic or harmful content will be allowed to stay online [2]. This practice may put non-Western users at disproportionately higher risks of encountering hate speech and disinformation or having their content wrongfully removed.

This study aimed to examine what sort of linguistic inaccuracy and inequity might result from the use of automated translation tools. We conducted a survey experiment where pieces of problematic content in Mandarin (retrieved from FBarchive document no. odoc4825423271w32, image 110475) were presented to both English and Mandarin speakers. English speakers were shown a translated version of the problematic content, while Mandarin speakers viewed the content in its original language. The results revealed that translating non-English content into English using an automated translation tool results in a significant discrepancy in users’ perception of the content’s harmfulness. This result highlights the linguistic inequity in platforms that are not optimized for non-Western user bases: On these platforms, non-English content may be wrongfully removed. Conversely, problematic content may be improperly overlooked and allowed to remain on the platform.

Based on these findings, we recommend that Facebook adopt a complementary approach to its current content moderation oversight. This approach would involve randomly selecting users who speak and understand the language of the flagged content to determine whether content is permissible. These users could share their perspectives by responding to a multiple-choice question on how the content should be moderated, utilizing Facebook's existing survey function. Their input would be incorporated into the final content moderation decision, helping to mitigate linguistic inaccuracies in the platform’s content moderation process. Such a practice might address another criticism of Facebook’s content moderation: inadequate inclusion of users’ voices in decision making.

Mandarin version of this abstract:

Facebook 長期以來因其看似任意的內容決策以及在決策中未充分考慮用戶的聲音而受到批評。 從該公司外流的文件顯示,Facebook 平台使用自動翻譯工具,將非英語內容翻譯成英語供審查者做出內容決策。使用自動翻譯工具可能會對非英語內容產生不準確的翻譯,導致內容被錯誤刪除,或者有害的內容被允許留在網路上。本文旨在說明由於使用自動翻譯工具而導致的語言不準確和不平等。我們進行了問卷實驗,向講英語和講中文的人展示相同的有問題的內容(取自文件編號 odoc4825423271w32, 圖片110475)。具體來說,向英語使用者展示有問題內容的翻譯版本,而向中文使用者展示其原始語言的內容。結果顯示,當使用自動翻譯工具將非英語內容翻譯成英語時,使用者對內容的不同語言版本之間的危害性的感知有顯著差異。這凸顯了語言不平等的問題,非英語內容可能會被錯誤地刪除,或者相反,有問題的內容可能會被不當忽視並允許保留在平台上

基於這些發現,我們建議 Facebook 可以利用該平台現有的調查功能,讓用戶透過回答有關如何審核內容的多選題來分享他們的觀點。他們的意見將被納入最終的內容審核決策中,有助於減少語言錯誤,並確保在平台的內容審核過程中考慮本地用戶的觀點。

Introduction

With Facebook’s user base exceeding 3 billion (as of 2023) [3], concerns about the platform’s seemingly arbitrary moderation of users' speech have continued to grow [4]. The platform faces a shortage of human content moderators and has increasingly relied on automated content moderation algorithms [5]. By its own count, as of 2019 Facebook had operational hate speech detection algorithms (referred to internally as "classifiers") for over 40 languages around the world and was using these to automate content moderation [6]. However, this automated approach has frequently led to errors, especially when applied to non-English languages.

1. Issues with Automated Moderation

Facebook's reliance on automated moderation tools has been problematic, particularly in non-English contexts. In one notable case, posts in Egyptian Arabic by a broadcaster criticizing a cleric were incorrectly flagged as promoting terrorism. According to an internal Facebook document, algorithms designed to detect terrorist content in Arabic misclassified content 77% of the time in the MENA region [7]. This example illustrates how these algorithms lack familiarity with local dialects and cultural context, resulting in significant errors.

Similarly, in India—Facebook’s largest user base [3]—the content moderation algorithm in 2019 only supported 4 of the country’s 22 official languages, leaving vast linguistic gaps and compromising moderation accuracy [6]. A similar issue exists for Mandarin-speaking users, where Facebook uses classifiers for content moderation but struggles to manage the complexities of the character-based language.

2. Human Moderation Without Local Context

While Facebook does utilize human content reviewers to complement its automated systems, the lack of local context and regional understanding often compromises their effectiveness. In the Mandarin-speaking world, for example, a Facebook public policy manager disclosed that most content reviewers for Mandarin-language posts are based in Singapore [8]. However, much of the content originates from Taiwan and Hong Kong, regions with distinct linguistic and cultural nuances. This geographic and contextual disconnect raises concerns about the accuracy of moderation decisions.

In India, where Facebook’s linguistic diversity presents a major challenge, the limited language coverage further underscores the platform’s inability to effectively moderate content across all user groups. Human moderators without the necessary local knowledge may misinterpret content, leading to the wrongful removal of posts or the failure to address problematic content appropriately.

3. Human Moderation with Machine Translation

A leaked document (retrieved from FBarchive document no. odoc4825423271w32, image 110475) from a Facebook whistleblower revealed another layer of complexity: Facebook uses automated translation tools to convert non-English borderline content into English so that human reviewers can make moderation decisions. This reliance on machine translation, however, introduces additional risks, as automated translation often strips away crucial context. The result is biased or inaccurate moderation, with English-speaking reviewers making decisions based on flawed translations. When local context is lost in translation, human reviewers are left with an incomplete picture, leading to errors in moderation decisions.

These issues—automated moderation errors, human moderation without local context, and the pitfalls of human moderation with machine translation—highlight the linguistic inequities embedded in Facebook’s content moderation practices [4] The over-reliance on automated tools, coupled with a lack of regionally informed human moderators, has led to the wrongful removal of content in many instances. This centralized, top-down approach to moderation has been criticized as arbitrary and undemocratic, further entrenching concerns about fairness and user inclusion.

Drawing on the information from leaked Facebook documents in FBarchive (document no. odoc4825423271w32, image 110475), this study sought to investigate the accuracy issues stemming from reliance on automated translation tools. Specifically, we explored whether the perceived permissibility of content changes when non-English content is translated into English using machine translation tools. Our case study focused on Mandarin-language content, examining whether the same piece of content was perceived differently by Mandarin- and English-speaking users after it was translated into English via Google Translate, as revealed in the FBarchive.

Background

Current state of content moderation practices and the role of users in the process

Issues around content moderation by digital platforms have garnered significant attention in recent years, with a particular focus being the role of user participation in the moderation process. Although any Facebook user can currently “flag” a piece of content, the impact of that action can vary [9]. User flagging carries the risk of being used as a form of trolling.

Facebook's content moderators often operate in “outsourced, industrialized, call center–like offices” situated in regions where labor costs are significantly lower than in the United States [10]. The internal documents in the FBarchive indicate that Facebook had not hired a sufficient number of staff to achieve the understanding of local political and cultural contexts that would be essential for making informed content moderation decisions [11]. S. T. Roberts' 2019 investigation revealed that the company tended to rely on frontline generalists employed by third-party contracting companies to make these critical decisions [12]. Documents in the FBarchive (document no. odoc4825423271w32, image 110475) further revealed that, in the case of non-English content, Facebook has resorted to automated translation using Google Translate, leading to a high level of inaccuracy (though the exact rate of inaccuracy was not disclosed).

One solution to the challenges of content moderation is providing users with meaningful avenues to appeal content removal or account suspension. In 2020, Facebook introduced a new feature enabling users to challenge content decisions they disagree with through an independent "Oversight Board," which holds the ultimate authority on whether the content should be retained or removed [13]. Content cases reach the Oversight Board for review through three channels: appeals by individuals, case referrals by Meta, and requests for Policy Advisory Opinions (PAOs). While users of Facebook and Instagram can directly appeal Meta’s content enforcement decisions to the board, in 2023 the Oversight Board received nearly 400,000 appeals but was able to provide decisions for only 53 cases [14]. Although the exact number of appealed cases remains unknown, it is reasonable to deduce that the cases appealed outnumber those reviewed by the Board, given the small number of cases reviewed.

The expansion of the channel available for user participation in content decisions did not subdue criticisms of Facebook’s content decisions and lack of inclusion of users’ voices. The appeal system is a protracted process: Before appealing a decision to the oversight board, users must first seek a review from Facebook's human reviewers [13].

The company occasionally cites a lack of available reviewers, providing various reasons (such as the COVID-19 outbreak). When there is a shortage of reviewers, Facebook says they prioritize review of content that they deem to have the highest potential for harm [15]. The exact criteria for determining what constitutes "harm" remain unclear. In this light, users whose content is taken down in error have few effective paths of redress Given the sheer volume of content, if a user appeals a content moderation decision and exhausts the review process, there is no guarantee that the case will reach the Oversight Board given the sheer volume of content appeals [16]. This reality underscores the importance of improving the accuracy of the platform's moderation mechanisms.

Participatory Approaches in Content Moderation

Applying participatory principles to content moderation is a relatively new but increasingly important development. Digital platforms such as Facebook and Twitter/X face immense challenges in moderating content at scale, particularly when it comes to balancing free expression with the need to protect users from harmful content. Top-down approaches, where content decisions are made by a small group of moderators or automated systems, have often been criticized for lacking transparency, accountability, and sensitivity to cultural and contextual nuances [17].

Generally, a participatory approach to policy decision-making has been considered to augment legitimacy and furnish an educational advantage that heightens civic cognizance of the policy formulation and appraisal process [18, 19]. Meta has in fact been a pioneer in considering this approach and exploring user engagement in platform governance. Its most recent attempt is the "Global Deliberative Polls." In November 2022, Meta hosted a “Community Forum.” The process was designed to “bring together diverse groups of people from all over the world to discuss tough issues, consider hard choices, and share their perspectives on a set of recommendations that could improve the experiences people have across our apps and technologies every day [20].” Conducted in collaboration with Stanford’s Deliberative Democracy Lab on the topic of bullying and harassment, the “Community Forum” was a first-of-its-kind experiment in participatory platform governance [21].

While this initiative is commendable, its impact on Facebook’s practices remains unclear. The decisions and recommendations arising from such forums may still face challenges in being translated into actionable policies, especially within the complex and rapidly evolving ecosystem of digital platforms.

The objective of this study is to lay the groundwork for Meta to integrate user feedback directly into the content moderation process. While broader deliberative practices often focus on policy recommendations that can be challenging to implement immediately, the experiment conducted in this study seeks to address a critical question that could lead to more actionable policy changes using Facebook's existing survey function: does involving local users enhance the accuracy of current content moderation practices? If the perception of the same piece of content varies among language users before and after it is translated by an automated tool, it will emphasize the importance of including local language users in the moderation process to ensure more accurate and culturally informed decisions.

Methods

Facebook Content

A leaked Facebook (now Meta) document from 2022 reveals that Facebook faced a language deficit in content moderators and turned to automated translation tools to translate non-English content for the purpose of content moderation. Stage 2 of our experiment involves testing whether or not English speakers are able to detect potentially problematic Mandarin content that has been translated to English using an automated translation tool.

In our survey, we utilized real content from the Facebook whistleblower's leaked document, which included Mandarin content flagged as borderline problematic on the platform. Each piece of Mandarin content was accompanied by an English translation produced by Facebook using Google Translate, as shown in FBarchive. For each of these pieces of content, one of our researchers, a native Mandarin speaker, provided a verifiable English translation of the Mandarin content, which we label below with “real meaning”. Our survey presented the English translation (produced by Facebook using Google Translate) of the content to English speakers and asked them to determine whether it violated Facebook's Community Guideline on objectionable content. We did not show the “real meaning” English translation to survey respondents.

Survey Design

- To compare the two languages, we administered surveys in both English and Mandarin. We created and hosted the English survey on SurveyMonkey and distributed it on the same platform to achieve a randomized sample of N=100 respondents based in the United States.

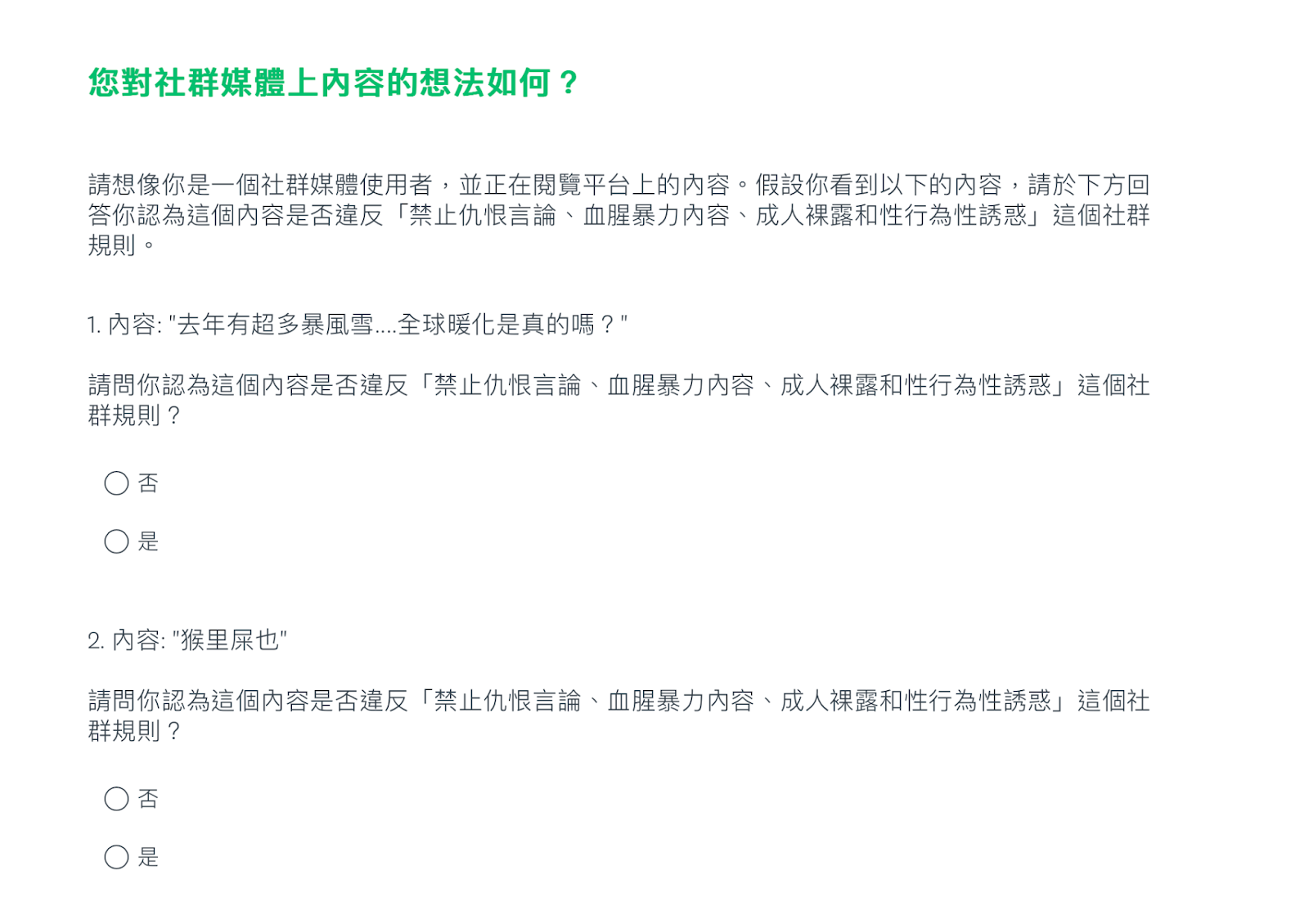

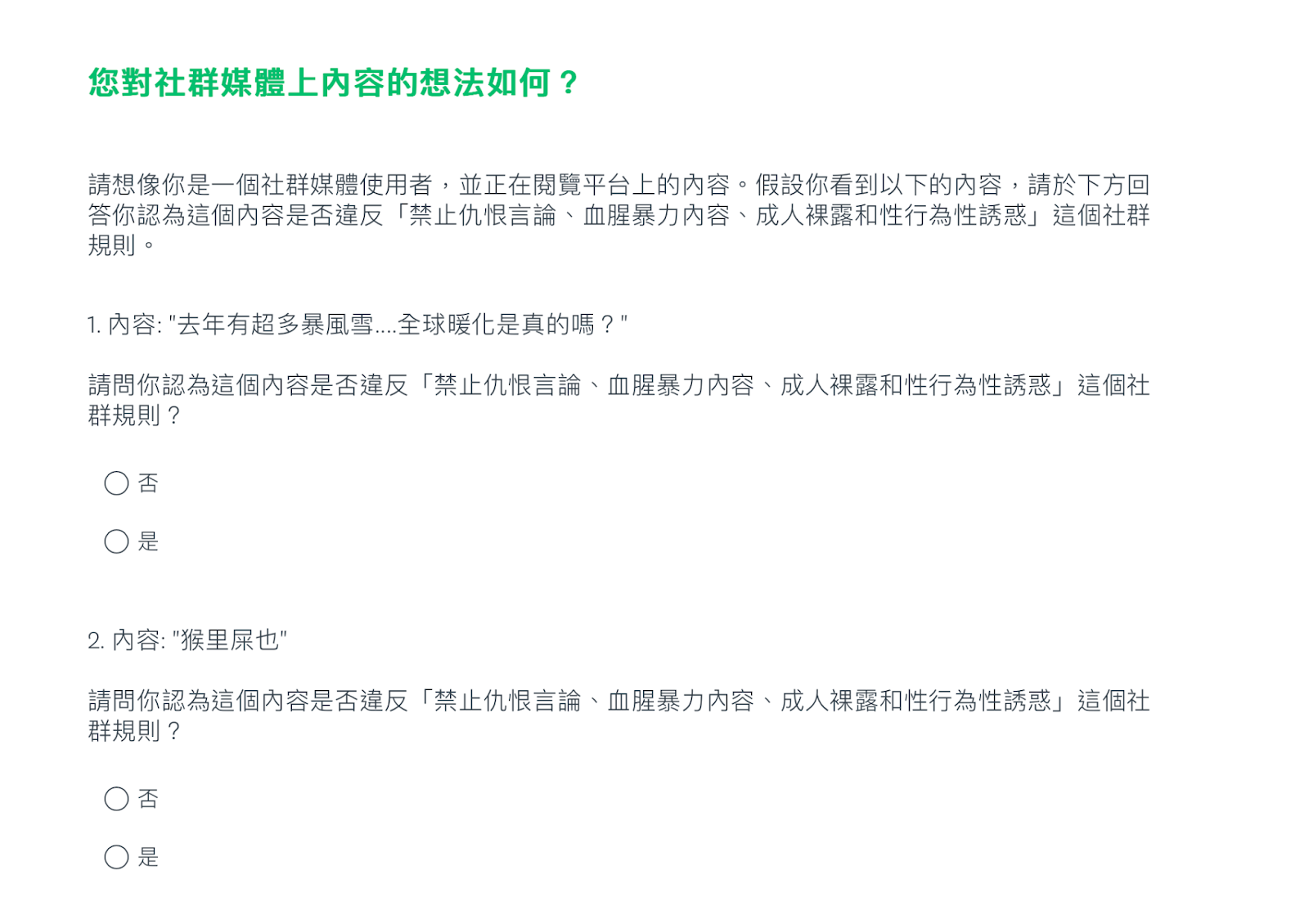

- For the Mandarin survey, we utilized Rakuten, an Asian service similar to Amazon Mechanical Turk in the U.S. The survey was conducted entirely in Mandarin and distributed to native Mandarin speakers based in Taiwan.

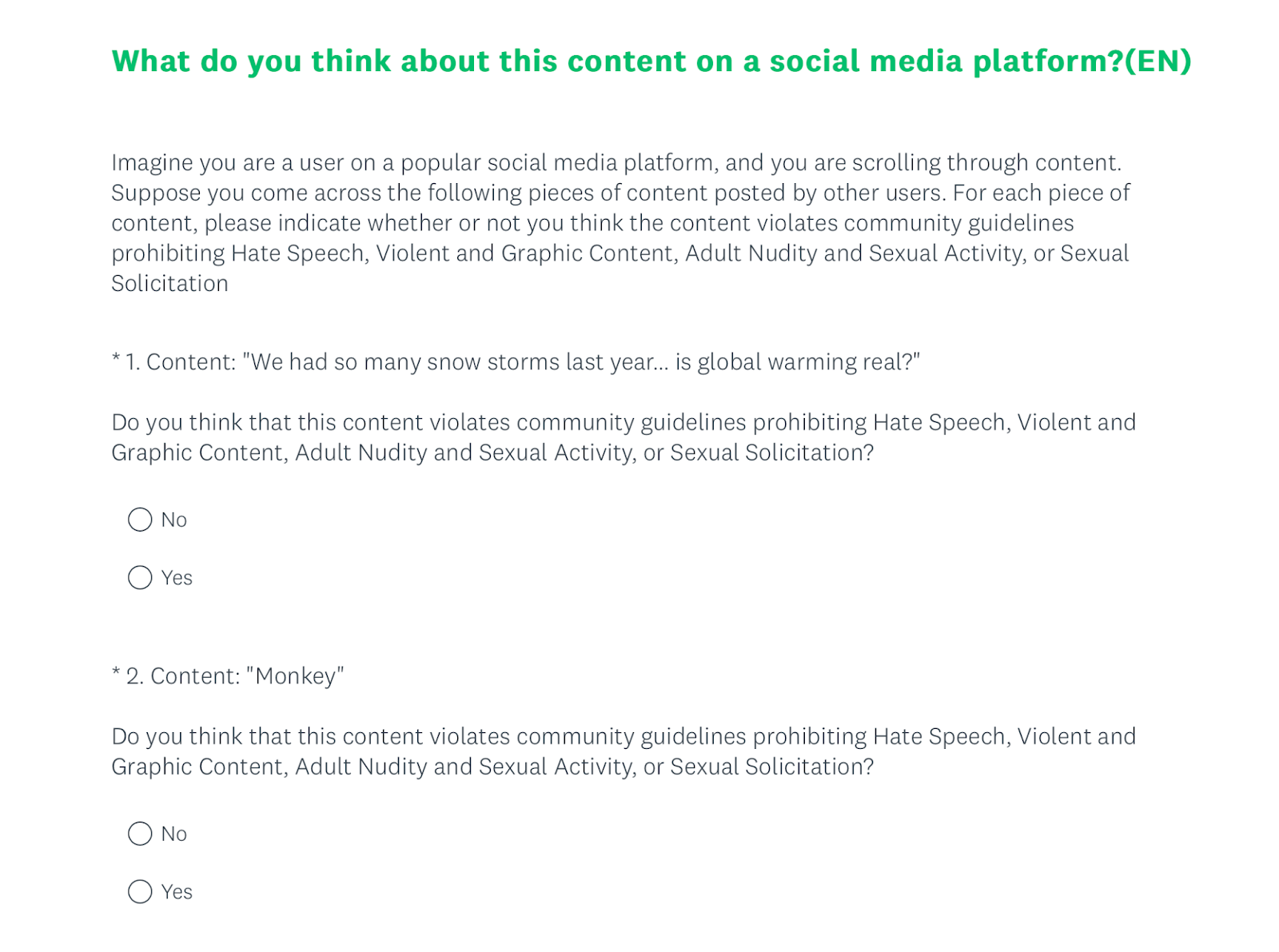

- To ensure the validity of the survey responses, we included attention checking/data quality checking questions, which we will refer to as “control questions,” in our survey to make sure that users are consciously answering the questions. The exact survey is as follows.

Survey Instrument

The following introduction was given to respondents at the beginning of the survey:

Imagine you are a user on a popular social media platform, and you are scrolling through the news feed. Suppose you come across the following pieces of content posted by other users. For each piece of content, please answer the following question:

“Do you think that this content violates community guidelines prohibiting Hate Speech, Violent and Graphic Content, Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity, or Sexual Solicitation?”

Content Used in Survey

Treatment questions (From FBarchive document no. odoc4825423271w32, image 110475)

- Mandarin version: 猴里屎也

English translation (from FBarchive): Monkey

(Real meaning: You go die) - Mandarin version: 死忠粉絲阿

English translation (from FBarchive): Die loyal fans

(Real meaning: Dead Chung’s fans) - Mandarin version: 賊婆

English translation (from FBarchive): thief

(Real meaning: Devious woman) - Mandarin version: 陣頭、衣服脫掉就是流氓!

English translation (from FBarchive): When you don't have clothes, you’re basically a thug

(Real meaning: Zhentou, they are hooligans when taking clothes off!)

Control Questions

We included data quality checking questions in both English and Mandarin surveys for the purpose of quality control and attention checking among the survey respondents. These questions presented innocuous content that was clearly not in violation of community guidelines. We would expect that respondents who were answering logically would answer “No” when asked if the content in the control questions violated the platform’s community guidelines.

Control Questions

- We had so many snow storms last year… is global warming real?

去年有超多暴風雪....全球暖化是真的嗎? - Happy Birthday, son!

兒子,生日快樂! - I don’t believe a word that person says.

我不相信他說的任何一個字 - I received my COVID booster shot and my flu shot today #getvaccinated.

我今天接種了新冠肺炎疫苗跟流感疫苗 #打疫苗 - So upset!

超沮喪!

We interleaved the treatment and control questions in the survey form. The questions appeared in the following order:

- We had so many snow storms last year… is global warming real?

- Monkey

- I received my COVID booster shot and my flu shot today #getvaccinated.

- So upset!

- Thief

- I don’t believe a word that person says.

- When you don't have clothes, you’re basically a thug

- Die loyal fans

- Happy Birthday, son!

Results

Quality Check Results

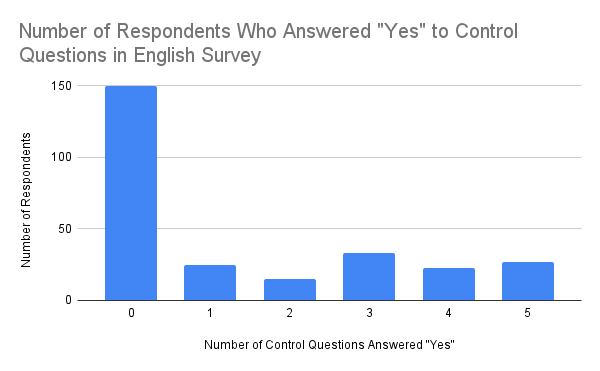

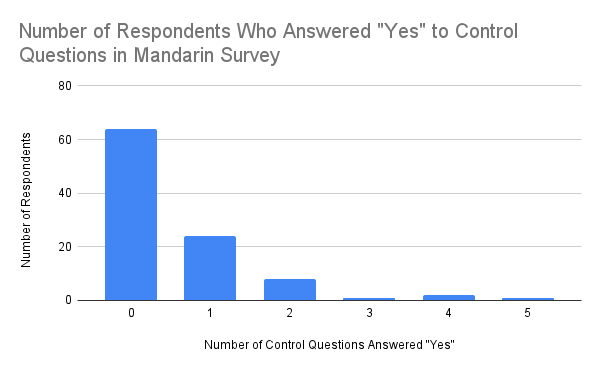

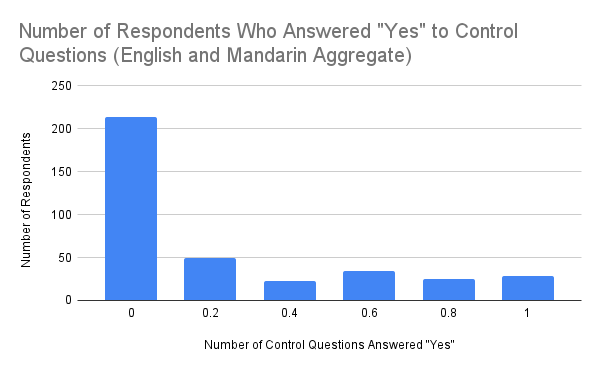

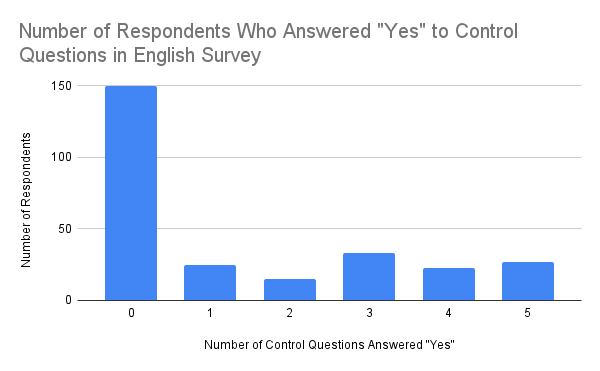

When exploring our survey results, we looked at the number of control questions that each individual answered “Yes” to. We did this for the Mandarin survey, the English survey, and the aggregate results of both surveys. We found the following:

The expectation was that respondents would answer “Yes” to zero control questions, because the control questions were designed to be innocuous and respondents were asked if they thought the statement violated community guidelines. The control questions, however, were not always viewed as clear, non-violating content. As seen in Figures 1 through 3, some respondents in each group answered “Yes” to two or more control questions.

Noting that the majority of respondents responded “Yes” to zero or 1 of the control questions, we decided to allow for one ambiguous control question. We removed from our sample any respondents who responded “Yes” to two or more. Following this data cleaning, we had a total of 175 respondents for the English survey (N1 = 175) and 88 respondents for the Mandarin survey (N2 = 88).

Figure 1. Number of Survey Respondents Who Answered “Yes” to Control Questions in English Survey

For the English survey, 175 out of 274 respondents (64%) answered “Yes” to fewer than 2 control questions (the expected answer to the control questions is “No”).

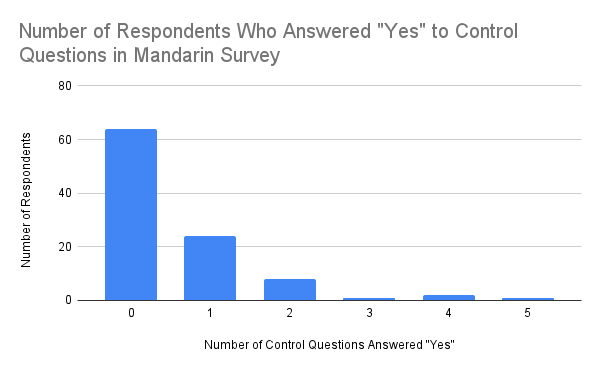

Figure 2. Number of Survey Respondents Who Answered “Yes” to Control Questions in Mandarin Survey

For the Mandarin survey, 88 out of 100 (88%) respondents answered “Yes” to fewer than 2 control questions (the expected answer to the control questions is “No”).

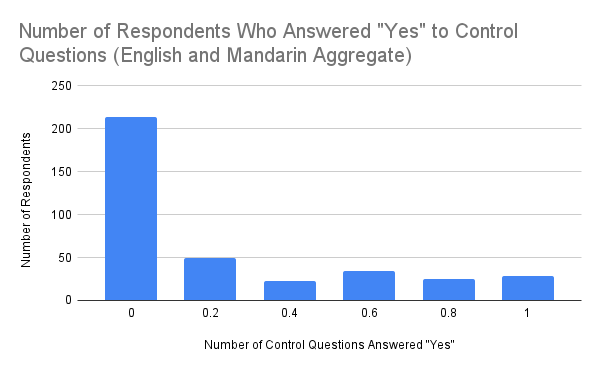

Figure 3. Number of Survey Respondents Who Answered “Yes” to Control Questions (English and Mandarin Aggregate)

Across the two surveys, 263 out of 374 (70%) respondents answered “Yes” to fewer than 2 control questions (the expected answer to the control questions is “No”).

Survey Results

In this section, we analyze the results of the Mandarin and English surveys to investigate whether or not there was a difference in how content permissibility was perceived between the two treatments: reading the content in its original Mandarin form, or reading the content translated to English via Google Translate. We analyzed the disaggregated results, comparing results for each treatment question in the Mandarin survey to results for the corresponding question in the English survey. We then compared the aggregate results for the Mandarin survey to the aggregate results for the English survey. Below is our analysis:

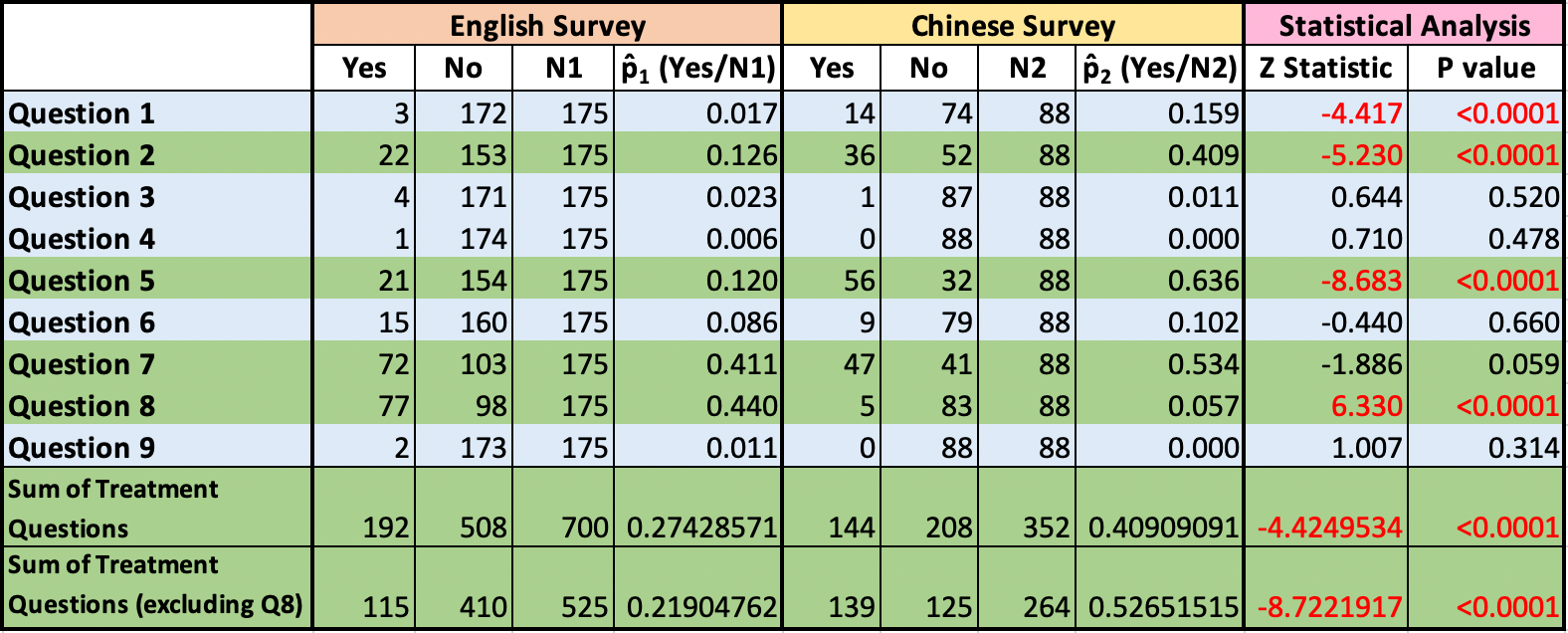

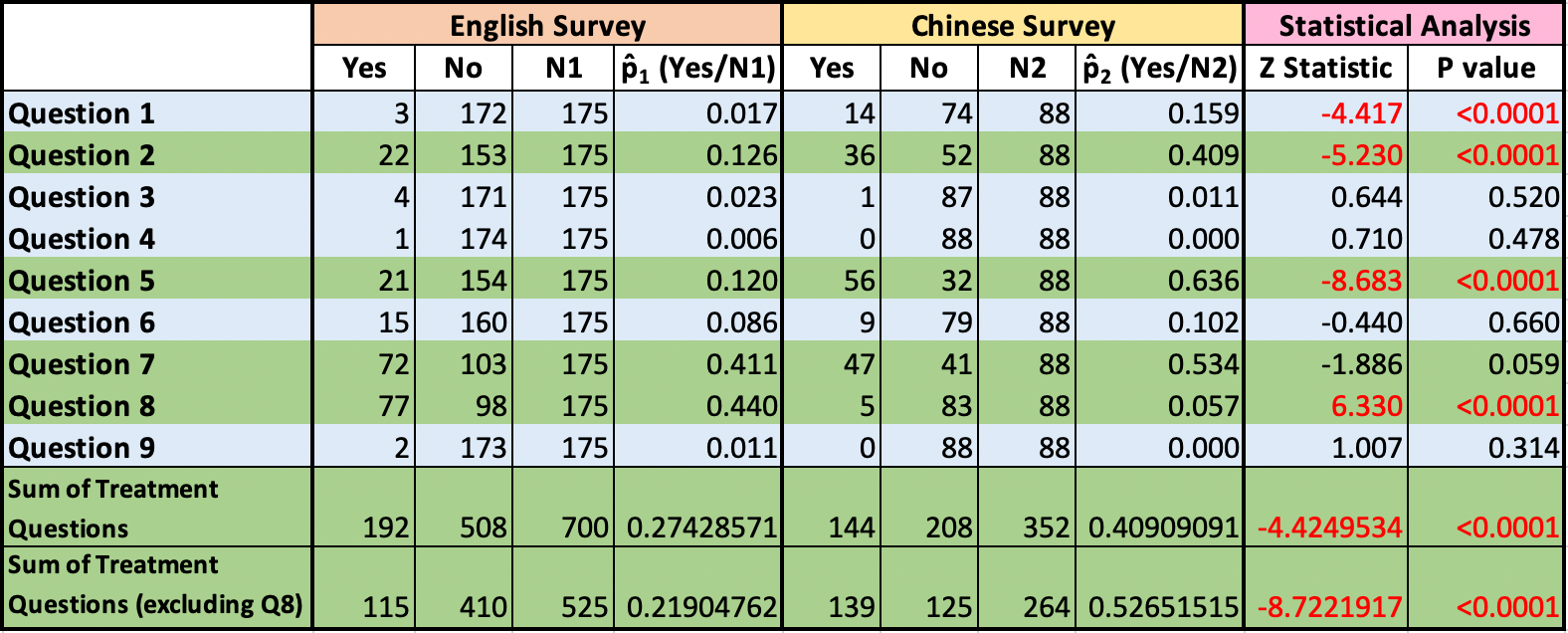

Figure 4: Survey Results and Statistical Analysis

Analysis I: Disaggregated Results

Figure 4 displays the results of our surveys, showing how many respondents answered “Yes” and how many answered “No” to each question in the English and Mandarin versions. A “Yes” answer signified that the respondent found the question content to be in violation of community guidelines for a social media platform.

We began by investigating the results question by question. We did a series of nine Z-tests to test the difference in responses between the English and Mandarin results for each question. Our null hypothesis for each test was that the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” to Question X in the English version of the survey (p̂1) would equal the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” to Question X in the Mandarin version of the survey (p̂2 ). We used a Two Sample Z Test for Proportions for each hypothesis test.

H0: p̂1 - p̂2 = 0

HA: p̂1 - p̂2 ≠ 0

As seen in Figure 4, we reject the null hypothesis for three of the four treatment questions: 2, 5, and 8 (see figures under “Statistical Analysis” column of Figure 4). In those three cases, there is a statistically significant difference between the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” to Question X in the English survey and the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” to Question X in the Mandarin survey.

Analysis II: Aggregate of English and Mandarin Surveys

Next, we compared the aggregated results of each survey. We summed the numbers of “Yes” and “No” responses across all treatment questions (Questions 2, 5, 7, and 8), which produced the result shown in the “Sum of Treatment Questions” row of Figure 4. We then conducted a Z-test that tested the difference between Mandarin and English results for the sum of the treatment questions. In other words, we tested whether the proportion of "Yes" responses across all treatment questions in the English Survey was equal to the proportion of "Yes" responses across all treatment questions in the Mandarin Survey.

Our null hypothesis was that the proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” to questions in the English version of the survey (p̂1) would equal the proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” to questions in the Mandarin version of the survey (p̂2 ).

H0: p̂1 - p̂2 = 0

HA: p̂1 - p̂2 ≠ 0

We found a statistically significant difference between the aggregate proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” in the English version of the survey and the aggregate proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” in the Mandarin version of the survey (z = -4.42, p < .001).

It was interesting to note the direction of the difference in proportions. In three out of four cases, the Mandarin version was more likely to be deemed objectionable than the English translation. In the fourth case, the Mandarin version was less likely to be deemed objectionable. Specifically, for Treatment Questions 2, 5, and 7, the proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” in the Mandarin version of the survey is greater than the proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” in the English version of the survey (p̂2 > p̂1). For Treatment Question 8, however, the proportion of respondents who answered “Yes” is greater in the English version of the survey than in the Mandarin version of the survey (p̂1 > p̂2). This directional difference in the Question 8 results reduced the calculated magnitude of the difference in proportions in Analysis II. Due to this directional difference, the magnitude of the difference is more significant in Analysis I. While differences are quite striking when looking at individual questions, summing all of the responses somewhat obscures those differences.

Discussion

Automated Translations in Content Moderation

Through our survey experiment, we find that when content is translated using an automated tool, viewers’ assessments of its permissibility changes. Specifically, we observed that in three out of four cases, when problematic Mandarin content was translated to English using an automated translation tool, the resulting English content was perceived to be permissible. In a fourth case, the English-language reviewers were more likely to see the content as problematic. In all cases there were perceived changes in permissibility for English-speaking viewers when problematic non-English content was translated into English using an automated translation tool.

The findings suggest that relying on automated translation tools can result in inaccurate and ineffective moderation of non-English content. English-speaking moderators who review content translated by these tools may make misguided decisions due to translation inaccuracies and a lack of cultural context. This finding reinforces arguments that the current content moderation system, due to inadequate resource investment, risks exacerbating global inequity (see, for example, Roberts, 2019). Based on information revealed in FBarchive, our study specifically adds to this body of literature by demonstrating that this issue can arise from an approach that prioritizes the perspectives of English speakers in the moderation process and fails to allocate adequate resources to non-English user bases.

Incorporating a participatory approach to content moderation decision-making

Adopting a participatory approach to content moderation could address the issue of neglecting local language and content due to reliance on automated tools. This approach would recognize the diverse linguistic and cultural landscape of online communities, empowering users who are fluent in local languages and familiar with regional nuances to participate in content moderation. We suggest that, by incorporating a participatory approach to content moderation decision-making, platforms can ensure that content is evaluated accurately within its cultural context and bridge the gap between global moderation policies and local community expectations. Moreover, such a process can potentially enhance transparency and accountability, as users would be actively engaged and empowered to influence content moderation decisions.

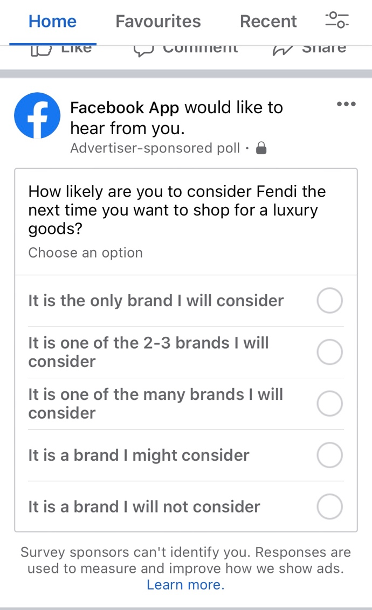

Figure 5. Facebook’s existing public survey function could be the vehicle (Facebook would gather user feedback on content using this feature)

Conclusion

Designing effective content moderation strategies is a complex task that requires careful consideration of multiple factors. Our experiments indicated that the current use of automated translation tools for content moderation is insufficient and inaccurate even when human reviewers extensively review translated content, as the perceived permissibility of content changes when translated via these tools. This finding highlights the urgent need to incorporate a participatory approach to content moderation decision-making, which could offer a scalable solution to Facebook’s shortage of content moderators proficient in non-English languages and contexts.

Specifically, our recommendation to adopt a participatory approach addresses two key issues with Facebook’s current content moderation methodology: its lack of democratic accountability and its inaccuracies due to insufficient understanding of linguistic and cultural contexts. Through this mechanism, a content item would be included in a public survey, where a number of users from the same region and language group would be randomly selected to provide their input. Their feedback would then be incorporated into the final content moderation decision. This approach aims to address these issues by involving users in moderating ambiguous content, thereby amplifying their voices and enhancing the accuracy of moderation decisions through better integration of linguistic and cultural context.

References

- F. Patel and L. Hecht-Felella, “Facebook’s Content Moderation Rules Are a Mess.” Brennan Center for Justice, Feb. 22, 2021. Accessed: Apr. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/facebooks-content-moderation-rules-are-mess

- I. Debris and F. Akram, “Facebook’s language gaps lets through hate-filled posts while blocking inoffensive content,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 25, 2021. Accessed: Oct. 25, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-10-25/facebook-language-gap-poor-screening-content]

- Statista, “Number of daily active Facebook users worldwide as of 4th quarter 2023,” statista.com. https://www.statista.com/statistics/346167/facebook-global-dau/ (accessed Dec. 12, 2024).

- C. Allen, “Facebook’s Content Moderation Failures in Ethiopia.” cfr.org, Apr. 19, 2022. Accessed: May 9, 2023. [Online]. Available; https://www.cfr.org/blog/facebooks-content-moderation-failures-ethiopia.

- R. Gorwa, R. Binns, and C. Katzenbach, “Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance,” Big Data & Society, volume 7, no. 1, Jan. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

- B. Perrigo, “Facebook Says It’s Removing More Hate Speech Than Ever Before. But There’s a Catch.” time.com, updated Nov. 27, 2019. Accessed: Aug. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://time.com/5739688/facebook-hate-speech-languages/

- T. Simonite, “Facebook Is Everywhere; Its Moderation Is Nowhere Close,” wired.com, Oct. 25, 2021. Accessed: Nov. 17, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.com/story/facebooks-global-reach-exceeds-linguistic-grasp/

- Central News Agency, “Content reviewers overseeing posts in Mandarin are mostly based in Singapore.” cna.com. https://www.cna.com.tw/news/ait/202201175011.aspx (accessed Jan. 17, 2022).

- K. Crawford and T. Gillespie, “What is a flag for? Social media reporting tools and the vocabulary of complaint,” News Media & Society, volume 16, no. 3, pp. 410-428, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814543163

- S. T. Roberts, Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvhrcz0v

- E. Culliford and B. Heath, “Language Gaps in Facebook’s Content Moderation System Allowed Abusive Posts on Platform: Report.” thewire.in. https://thewire.in/tech/facebook-content-moderation-language-gap-abusive-posts (accessed Oct. 26, 2021).

- S. T. Roberts, Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019, pp. 170-200.

- Facebook, “How Do I Appeal Facebook’s Content Decision to the Oversight Board?,” facebook.com. https://www.facebook.com/help/346366453115924 (accessed Apr. 24, 2019).

- Meta, Oversight Board 2023 Annual Report. https://www.oversightboard.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Oversight-Board-2023-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed Dec. 18, 2024)

- Facebook, “I don’t think Facebook should have taken down my post,” facebook.com. https://www.facebook.com/help/2090856331203011?helpref=faq_content (accessed May 13, 2022).

- E. Bell, “Facebook’s Oversight Board plays it safe,” Columbia Journalism Review. December 2, 2020. Accessed Aug. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/facebook-oversight-board.php

- G. De Gregorio, “Democratising online content moderation: A constitutional framework,” Computer Law & Security Review, volume 36, Apr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3474123

- A. Fung, E. O. Wright, and R. Abers. Deepening democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance. London; New York: Verso, 2003.

- E. O. Wright. Envisioning real utopias. London; New York: Verso, 2010.

- B. Harris, “Improving People’s Experiences Through Community Forums.” Meta Newsroom, Nov. 16, 2022. Accessed: Aug. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://about.fb.com/news/2022/11/improving-peoples-experiences-through-community-forums/

- J. S. Fishkin, A. Siu, S. Chang, E. Ciesla, T. Kartsang. (2023, June). “Metaverse Community Forum: Results Analysis,” Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University, June 22, 2023. Accessed: Dec. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/metaverse-community-forum-results-analysis

Appendix

English Survey Interface

Mandarin Survey Interface

Authors

Yi-Ting Lien currently serves as co-director of “Tech for Good Asia,” a technology-focused non-governmental organization dedicated to leveraging technology for the public good. She is also a research affiliate at the Public Interest Tech Lab at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, where she recently completed her Master’s in Public Policy. Prior to her studies at Harvard, Yi-Ting worked at Taiwan’s National Security Council and the Presidential Office, conducting policy research at the intersection of geopolitics and technology policy for the Taiwanese government. She also served as a campaign spokesperson during President Tsai Ing-wen’s successful bid for re-election in 2020.

Maya Vishwanath is a senior consultant and researcher with a background in digital government and technology policy. She is passionate about the intersection of technology, human rights, and public policy. Maya holds a Master’s in Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School (2023) and a B.S. in Quantitative Economics from Tufts University (2020).

Suggestions (0)

Click the below button to open the suggestions form in a new tab.

Enter your recommendation for follow-up or ongoing work in the box at the end of the page.

Feel free to provide ideas for next

steps, follow-on research, or other research inspired by this paper.

Perhaps someone will read your

comment, do the described work, and publish a paper about it. What do

you recommend as a next research step?

Submit Suggestion on MyPrivacyPolls

Back to Top